By Aili Cecilia García

“A man who cooks is very sexy. A woman who cooks is not that sexy. Because it’s associated in our mind to the domestic cliché of the woman” – Isabel Allende.

When I first came to Chile, where my father and his family were born and raised, I had lived all my life in Sweden, my mother’s home. There are no words to describe how excited I was, I’d heard so many stories about this miraculous country, a cultural goldmine that had fought its way through some very troubling times and was now developing rapidly. There are many Chileans in Sweden, and my family has always thought it obvious to incorporate us – the second generation of Chileans – into our cultural heritage, so I did not experience any significant culture clash when I arrived. What I soon realised, however, was nothing I had spent much time thinking about before.

Where was my place in this remarkable society? As I was getting to know some cousins I had never met before, we got into the subject of cooking and I revealed a horrible truth about myself: “I cannot cook.” I told them how I used to contribute with groceries and dishwashing to let my brother do the cooking for me and they were shocked to say the least. How was I to take care of the men in my life without being able to cook? Was there any man in my life? My answer, “No.” This was, if possible, even more appalling. The idea of a young girl without neither boyfriend nor husband, who was perfectly fine with the idea of remaining single seemed extremely confusing to these men. But after making a couple of jokes about it, they let go of the topic and seemed to accept my strange stand. After another couple of similar encounters, where I was told I could not possibly write poetry, or know anything about politics as a girl, I realised that ideas of this kind have always been present around me, reinforced, perhaps most strongly from my own grandmother. I need to cook and clean, sow and behave appropriately, and, to my horror as a tomboy child, I need to always look pretty, tidy, and female.

The traditional view of women as caretakers is upheld by men and women alike in Chile, and a 2010 UNDP study shows that as many as 62% of Chileans oppose full gender equality. The Latin-American “Machismo”-culture and religion steadily reinforce these ideas in Chile, but so does legislation. The Pinochet-led dictatorship promoted a policy-based return to traditional views of women. It encouraged the treatment of female workers as a secondary workforce and their discrimination in the workplace, while also maintaining the now outdated and scrapped marriage law. This law stated that, once married, the husband had rights over his wife and her assets, thus inheriting all of her wealth, but also, by law, her faithfulness and obedience. Before 2004, divorce was also unlawful in Chile. My grandmother experienced a lot of trouble with these laws. She divorced my grandfather in Sweden, but could not do so in Chile, which resulted in a long, still on-going battle of assets and territory between the two.

The new divorce law has also been crucial for women searching for a way to get out of abusive relationships in Chile. Larger financial decisions require the husband’s signature, thus women have been subject to financial manipulation by their husbands. Domestic violence has however been the more pressing issue, where, in 2004, 50% of Chilean women had suffered spousal abuse and more than half of these had been subject to physical violence.

“Here, they teach you to accept the lot you were given… Unfortunately we are a generation of repressed women . . . They teach you that marriage is for life and I was ashamed to admit that I had made a bad choice. And so I tried to maintain the relationship, hoping it would improve with time. But it only got worse.” These are the words of a woman who escaped her husband after he had threatened to kill her on Christmas Day almost 15 years ago.

Despite the 1994 Intrafamily Violence Law, sufficient means to address punishments for perpetrators and victim protection are still lacking due to the compromises that had to be made for the law to pass. A study made in 2004 shows that many women in Chile accept domestic violence as a normal occurrence due to its high prevalence in Chilean society. It thus becomes clearer how deeply these macho ideals are rooted in Chile – where many women accept their inferiority.

I was born in ancient times, at the end of the world, in a patriarchal Catholic and conservative family. No wonder that by age five I was a raging feminist – although the term had not reached Chile yet, so nobody knew what the heck was wrong with me” – Isabel Allende.

The most crucial problem facing Chilean women today however arguably falls under the title “reproductive rights.” The idea that women can only reach complete self-fulfilment through motherhood permeates Chilean culture and was also something I experienced first-hand during my visit in the country. Part of the alarm brought about with my own singlehood was that it meant I wasn’t in the process of having children – in Chile it is not atypical for girls to have their first child before turning 20 – often, it is rather the opposite. In the case of my own family, this has led to a few experiences of single motherhood, where relatives of mine have faced extremely hard times trying to pursue their own goals in life with a baby on their arm. Traditional beliefs about women’s roles as mothers have contributed to the rarity of sex education in schools and women’s unlikeliness to use contraceptives.

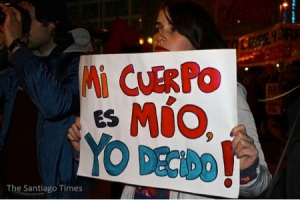

The distribution of emergency contraception was, in fact, recently completely outlawed by the Chilean government. Most detrimental to the well-being of women are, however, the abortion laws introduced during the dictatorship in 1989, which have been deemed amongst the strictest in the world. Chile is today one of five countries in the world banning abortion in all cases, even where the pregnancy endangers the woman’s life. Just two years ago an 11 year old girl was denied abortion despite being a victim of continual incidences of rape conducted by her mother’s partner. About 120-160,000 Chileans however pursue illegal abortions annually – abortions that are generally unsafe.

Last year’s appointment of Michelle Bachelet as President nevertheless bears promises for the future of women in Chile. Although the law she pushed through in 2006 to make emergency contraception available at state-run hospitals was reversed by the highest court in 2008, Bachelet’s 2013 election-campaign called for a relaxation of the abortion laws. During her first term in office she fostered opportunities for women through, for example, improving and expanding child care, making free child care centres four times more frequent, pension-reforms, and increasing the budget of the national institution dealing with Women’s rights (SERNAM). She also ensured that half of her cabinet were women.

In terms of women’s employment, Michelle further criminalised the request of gender-information on job applications and employer’s requests of pregnancy tests by their employees. Whereas Chilean women and men share similar attendance in higher education, only about 48% percent of the former are actually employed. Bachelet’s child care reforms, proved, in 2012, to have failed to impact on women’s participation in the workforce and most child care provisions remain unattainable for the poorer. Furthermore, the overall gender income gap stood, in 2007, at 33%, however among those with university degrees the pay gap rises to about 40%. This amounts to one of the worst pay gaps in the world.

In 2012, former minister Laura Albornoz stated: “When I was minister, whenever the male ministers told me that they had a lot of responsibilities, too, I’d ask them, what’s your family going to eat at home today? And they couldn’t answer because they’d never been on their way out the door, in the morning, and stopped to take a chicken out of the freezer, to thaw for dinner.”

The difficulties of being a mother while participating in the labour force are widely felt among women in Chile. A cousin of mine, with her child’s father absent when I last met her, was working three jobs during the day to earn her living, while studying night-time to pursue her career in medicine. Luckily for her, her mother had agreed to help care for the baby. Whereas there are indeed laws to favourably regulate the wages and working conditions of women in work, these are rarely applied in reality. Paid maternity leave is, for example, provided for women, but applies only to women in the formal sector with employment contracts – something many women still lack in Chile today.

Ultimately, the attitudes facing women in the workforce often remain discriminatory. Many of the difficulties Bachelet faced during her first term were often blamed on her gender by both men and women. Indeed, Chile maintains a relatively low number of women in Congress in comparison to the rest of South America.

As the former head of the United Nations organ directed to promote gender equality, and as a generally popular former president, Bachelet’s election-campaign demonstrated a more firm stand to promote women’s rights in Chile in the coming term. With a steady focus on equality and non-discrimination against women, Ms Bachelet is now provided the opportunity to improve the daily lives of women in Chile.

My experience with the Chilean way of reasoning about women has often led me to think of how lucky I am to have grown up in Sweden – the ‘ultimate model’ for women’s emancipation. Through encounters with people of other nationalities, and also through foreign and national media channels, I am repeatedly told of how ideal Sweden is for a woman. In 2000 Sweden was titled an ‘exemplary country’ by the UN when it comes to gender equality. And I tend to agree.

Sweden has one of the highest employment rates in the world for women, where according to the OECD about 72% of women are in paid employment in contrast to 76% of men. With special protection for part-time workers, laws restricting employers from firing women who have recently become mothers throughout their maternity leaves and further anti-discrimination policy measures for women in the workplace and in schools, it is hard to state otherwise. Swedish national television even assures equal amounts of airtime to women’s and men’s sports!

Public childcare is guaranteed to all parents, and fees are highly subsidized, with parents paying fees proportional to their income and their number of children, while facilities operate whole days (about 12h/day). In terms of parental leave, the Swedish model guarantees 13 months of leave paid at 80% of the most recent income, with an extra 3 months paid at a fixed rate for Swedish couples. Of these, each parent has a nonexchangeable claim to two months of compensated leave – with an additional economic incentive for more equal childcare called the ‘Gender equality bonus’ that relates to the take-up of parental leave benefits. Contraception is moreover free in youth clinics available in most cities, and can also be found at the school nurses’ office. Abortions are available to all women up to the 18th week of pregnancy, and there’s generally nothing controversial about it. In comparison to Chilean society, Sweden therefore seems like a heaven for women.

Personal experiences also tell me that the notion of equality is something accepted by most people. However, there appears to be a difference between adhering to a belief, or believing to do so, and actually acting by it in practice in Sweden. In the work sphere, women still earn, on average, 17% less than men. Moreover, three times as many women than men work part-time, less than a third of entrepreneurs are female and about as many women are in managerial positions, and women who work in Swedish corporate boards are often there due to quotas. The combination of part-time work and parental leave applicable to many women today means that women’s aggregate lifetime salaries in Sweden amount to about 330,000£ less than those of men.

According to the Globe and Mail the Swedish labour market also belongs to one of the most gender-segregated in the world. Linked to this, is, according to SKL, an organisation for employers and members of Swedish municipalities and counties, a structural wage discrimination where professions generally dominated by women are less valued than what are arguably equivalent occupations dominated by men. Examples of this are assistant nurses who earned about 240£ less than per month than machine-minders, and social welfare secretaries that earned around 1,100£ less than IT consultants in 2012.

Finally, despite the fact that Swedish men are increasingly taking up household-work and, according to one study, do more housework than men in the rest of the world, about 66% of this work is still performed by women. Women also tend to work less after having children, taking almost four times as much time off with their kids, where Swedish fathers for example utilise a mere 24% of the total time of parental leave. It thus becomes apparent that many spheres in Swedish society still need improvement for gender equality to fully take place. Old gender norms still apply, and affect people’s daily conducts, where, despite encouraging policy attempts to increase gender equality, men and women are still operating on different terms in society.

Viewing Sweden as the ‘ultimate model’ for women’s emancipation is therefore dangerous if the goal is equality. If even in highly progressive countries such as Sweden equality is still far away, feminism cannot be treated as a time-constrained issue, or something you achieve and can thereafter put a lid on. With regards to Sweden, people – me included – reinforce the idea that we have come very far in terms of gender equality, and in a comparative perspective to countries such as Chile, we have. However, to belaud Sweden can be detrimental to the country’s future successes, as could it be detrimental to do so in other progressive states. It is very easy to point at other countries and say that ‘in comparison, we are better, so why worry about the little things’. The problem is that these are not little things, although, in a comparative perspective they may seem to be. To consider the strife towards gender equality ‘finished’, or ‘almost finished’ business may even give room for the types of backwards progress visible in some European countries where abortion laws are on the agenda to be reintroduced in for example Spain. Feminism therefore needs to be treated as a constant, something that should be actively upheld, to see our societies prosper. This, until the day that our norms have fundamentally changed – something still far away, but absolutely achievable.

About the author:

Aili is an Undergraduate student of Politics at Glasgow University. She is passionate about human rights and does not believe in purely black and white portrayals of the world.