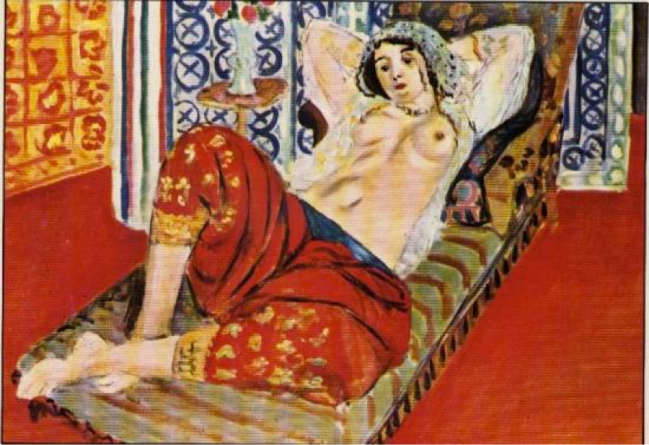

Bollywood actress Sonam Kapoor, known for being fashion forward, wore a nose ring (“nathani”) as the only piece of jewelry at Cannes Film Festival in 2013—presumably both as a style statement and a declaration of her “Indian-ness”.

By Tanvi Misra

Some women choose to wear the Islamic veil because it’s an expression of cultural identity rather than a symbol of patriarchy for them. It’s not exactly the same, but it’s quite similar to why I choose to wear a nose ring.

A lot of people, even South Asian women who have nose piercings, may not know the significance of a nose stud in Hinduism. A lot of people say it’s associated with goddess Parvati—the lady up there in charge of matrimony. Some apparently also believe that a piercing on the left side eases the pain of childbirth—something about it being linked to the reproductive organs.

Some women in India probably still do it for the above reasons; I don’t know any of them.

My friends and I got our noses pierced in high school. We did it because it was the safest form of rebellion for us—it wouldn’t alienate our teachers and parents because we could pass it off as traditional. But if we mixed it with western clothes, it felt like we were being subversive.

It seemed to be quite appropriate choice for our breed of post-colonial lost children with our Hinglish slang and Indo-western fashion trends. We were privileged enough to experience the “clash of civilizations” in our backyards, and we proudly wore the spoils.

For a lot of us girls especially, traditions were like hand-me-down clothes, we tried on what suited our personality and stuffed the rest at the back of a proverbial closet without knowing or caring about the context.

I myself have discarded several traditions without a second thought. The nose ring is not one of them because till today, it reminds me of my composite identity—of the peaceful coexistence of my Indian-ness and rebelliousness.

So when I look at Iranian hijabi women in this street fashion blog or that video showing American Muslimahs chilling to Jay-Z’s “SomewhereinAmerica,” I can relate.

I know the two aren’t the same, but there are undeniable parallels. They both have had a religious significance in a non-Western culture. They can both be viewed as endorsing historically patriarchal systems. They’re also both almost exclusively worn by women.

Now, to be clear, I don’t advocate being forced to wear a veil just like I’d really hate it if someone were running around forcibly piercing the noses of all South Asian girls. But I’d also be pretty annoyed if while working in London or France, some sort of self-righteous piercing police was trying to ban wearing nose rings in public.

What I do strongly advocate is that women be free to express themselves and their identities any way they choose—no matter where they are in the world, what their religion or skin color is.

For many of these women, the hijab is an association with the Muslim culture, customs or faith than with oppression and patriarchy. It exists in different avatars around the world, many of which are a part of the traditional dress of a region.

But the West has a hard time understanding it. Why would anyone wear it voluntarily? Because I wouldn’t, it might be easier for me to explain it away: they must be forced, and so the solution is to force them not to. I’m making so many assumptions about people in this case and offering a simplistic, logically flawed, solution. The actual reasons behind why women wear the hijab are much more complex and varied.

Laila Shaikley, one of the women behind the “Mipsters” (Muslim Hipsters) video, grew from an awkward, young skateboarder, to a trend-setting world-traveller. She worked with the organizations such as the UN and NASA, helped establish TEDxBaghdad and involved herself in social entrepreneurship around the world. In this article in The Atlantic, she talks about her decision to wear the hijab.

As I grew and changed, I faced one particular choice again and again: To represent my Muslim identity or to leave it for the easier world of religious anonymity. I chose to maintain my relationship with hijab.

This was Layla’s choice, just as it is my choice to wear a nose ring—just as it’s my college roommate’s choice to not wear a traditional white wedding dress and accompanying veil at her wedding.

This roommate, a white woman from North Carolina, explained to me the reason behind her choice.

It’s a little to do with the white dress and veil combo reinforcing patriarchal systems, but mostly, she doesn’t like the idea of weddings being these over-the-top celebrations of Disney values that little girls fantasize about.

“I have no interest in feeling like a princess. So it is a little about patriarchy, but also just an expression of my values and personality, which relate to my personal identity,” she said.

Why she has decided not to wear the dress and veil combo, is why a lot of women in the West—a lot of them feminists—decide to wear it. It ties them to tradition perhaps, and it’s compatible with their personalities.

Traditions, customs and rituals are changing as cultural contexts are evolving. Any element of expression—be it a word of a few meters of cloth— needs to be seen in the context it is used.

About the author:

I’m a journalist. I am currently writing features for BBC’s online news magazine and trying to graduate from the Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. I hope to be a successful adult soon after—so I’d love it if you offered me a job. I got my Bachelor’s degree in political science and French from the University of Pennsylvania—my parents are still wondering why. I am originally from New Delhi, India. One day, I will travel all over the world and do great things. But for now, I okay with wasting my time on the Internet while eating cheese. I used to be a dancer, but now I like to run—usually away from things. The last book I read was Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and it made me cry. At the moment, I am listening to a Modern Lovers album and pretending I don’t care about what you think.

Follow me on Twitter @Tanvim because then I’ll have more followers and that is good for my self-esteem.